The Observation

My weekends have changed.

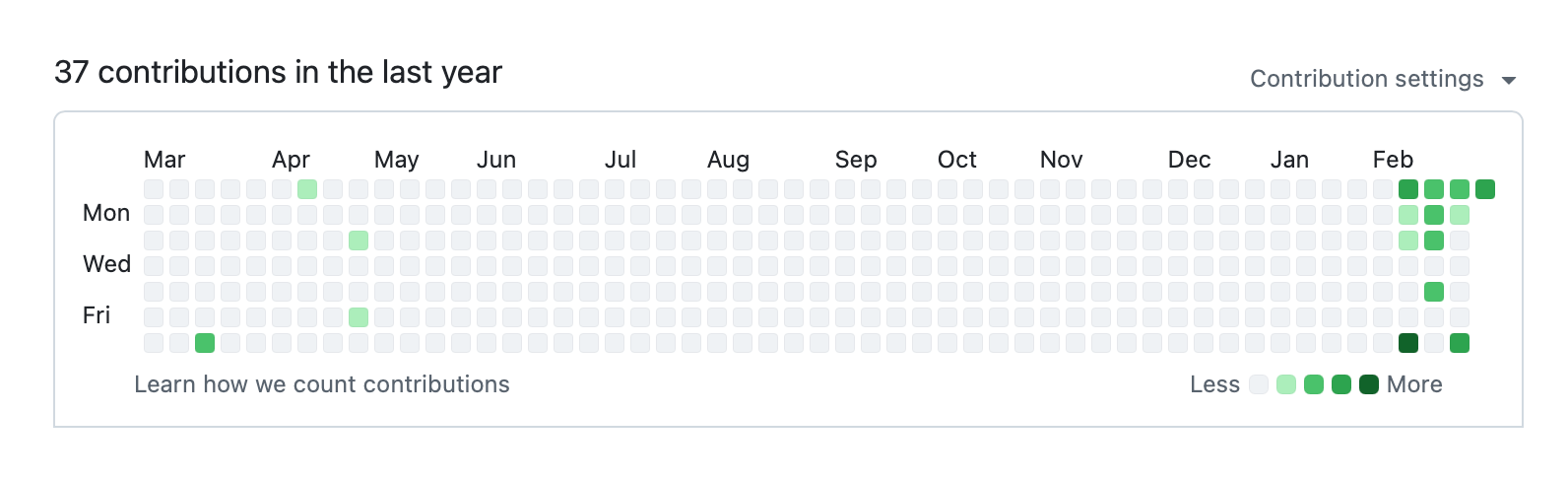

That change is best described by this image.

A mostly empty year, followed by a small cluster of green dots concentrated over a few weekends. No long streaks. No daily grind. Just bursts of activity when curiosity took over.

Those dots come from me using Codex and Claude Code over weekends—sometimes purely on my phone. These tools have quietly unlocked this behavior for me. The friction is low enough that I don’t need elaborate setups, agents, or even OpenClaw. The idea goes straight to an artifact.

If there’s one regret, it’s not using Claude Code earlier.

Around the same time, a post[^1] by Matt Shumer echoed a lot of what I was feeling. Another catalyst was Simon Willison’s recent write-up on building HTML tools with AI[^2]. Both pieces captured a shift I was already experiencing—and they prompted me to finally share some notes and reflections on what’s changing in my world.

The change

Six months ago, most of my interactions with AI looked familiar:

- Fix this bug

- Explain why this broke

That is no longer the case. AI coding has come a long way since then.

Today, like the folks at Spotify[^3], I find myself asking for things on the Claude app on my iPhone and approving PRs on the go.

For months now, I’ve been telling friends that writing code feels like breaking rocks. That feeling came from staring at raw output—lines and lines of code. We are well past that point now.

When generating 5,000 lines of code becomes cheap, the real value shifts to judgment. Instead of building one solution, I now build multiple variants—different approaches, different assumptions, different visual metaphors—and then pick and choose what feels right.

I build variants. I throw most of it away. I move on without regret. Code is cheap.

Variation has become a first-class part of exploration.

I am the bottleneck

Along the way, I noticed something uncomfortable: I was becoming the bottleneck.

I kept adding guardrails—often without realizing it.

I forced the AI to use a particular programming language simply because I was familiar with it, not because it was the best fit for the problem.

I suggested solutions when I wasn’t the expert—especially for problems like finding patterns or series in messy data with a lot of variation. I told it how to solve the problem instead of letting it explore what the solution space could look like.

I even constrained the output shape. I forced everything into a single page with a single chart, when the better solution turned out to be multiple pages with multiple charts—making it far easier to visually notice discrepancies and outliers.

In hindsight, these were all classic mistakes.

I was behaving like a consumer who insists on suggesting solutions to what might be the best product manager in the world. Once I stopped doing that—once I simply gave it the problem and stepped back—the quality of outcomes jumped immediately.

I wasn’t protecting the system. I was limiting the outcome.

⸻

This shift also forced me to confront some deeply ingrained product instincts.

As a product manager, I’ve spent years thinking in terms of effort and complexity:

- How much lift can an engineer do in a sprint?

- How complicated is this change?

- What is the fastest MVP I can get out the door?

Those questions once felt responsible. Lately, they feel like limiters.

When AI collapses effort, “how hard is this?” becomes a terrible proxy for value. Complexity stops being a risk signal and starts being something you worry about after the right solution is clear—not before.

If the solution is right, the path there matters far less than we’ve been trained to believe.

⸻

On the work side, I can now build functional prototypes and test them with customers before an engineer writes a single line of production code.

Not mockups! Not static flows! Real, working artifacts.

The most surprising part isn’t the capability—it’s the experience. There’s a strange joy in updating a prototype during a conversation. In saying, “What we just talked about is deployed—let me show you,” and watching a customer react to something that didn’t exist five minutes ago.

My tooling has evolved alongside this shift. Much of it is now self-built. I no longer pull data via Insomnia or Postman and analyze it in Excel. Instead, I use python scripts, DuckDB, and HTML dashboards—built with AI. I can iterate on them in real time, adding charts or reshaping the data as questions emerge.

The Next Constraint: Human Context Rot

One challenge I clearly foresee is context overload—on the human side.

There’s a lot of talk about generalists winning in an AI-enabled world. I broadly agree. But generalists still have limits. We can only hold so much context in our heads at once.

So the real question becomes: what is the upper bound of context a human can manage before it turns into burnout?

When everything is possible—when variants multiply effortlessly and every idea can spawn a dashboard or a prototype—what do we drop? What do we forget? What quietly rots in the background?

This is one reason I believe some form of a digital second brain will become essential. Not just note-taking or bookmarking, but systems that actively hold context for us—much like how swapping pages to disk allows an operating system to take on more load than physical memory alone.

These systems might not make us smarter, but they may allow us to carry a little more cognitive weight without collapsing. They might also make it easier to collaborate with AI by giving us a shared space to hold, manipulate, and revisit context.

Note taking finally matters

I don’t yet know what the right shape of this is. I do know that that notetaking (which I have writing about for years) is more important than ever.

I’m actively trying to move away from chat as the primary interface toward more persistent, document-based interactions. I want to refer back to conversations, extract insights, and build on them over time without losing the thread.

And I have an even harder question that I don’t yet have an answer to:

How do people entering digital or computer-based workflows get opportunities in this world?

When so much context is implicit, personal, and accumulated over time, how do newcomers plug in socially? How do they learn, contribute, and get noticed when the surface area keeps expanding but the entry points feel less visible?

End notes

I don’t think this is the final form of how we’ll work. I don’t even think I fully understand where it leads yet. But I do know I can’t unsee the shift.

When building becomes cheap, curiosity becomes the constraint. And now, context might be the next one.

[^1]: Something big is happening - Matt Shumer

[^2]: Useful patterns for building HTML tools - Simon Willison

[^3]: Spotify says its best developers haven’t written a line of code since December, thanks to AI